[This article is Part 3 of 3 on the topic of social reality. Start with Part 1 and Part 2.]

Imagine what would happen if everyone in the world suddenly agreed that we could magically walk through walls. TV news shows would run feature stories on this amazing new ability. Scientists might publish papers on the physics of walking through walls, while eager young YouTubers offered lessons on the best angles of approach. Fashion magazines would advertise the latest wall-walking outfits. Sales of doors would plummet.

In the physical world, however, walls are solid. Any would-be wall-walkers will encounter only headaches on impact, now matter how much we wish that “Platform 9-3/4” was real. We can tell any stories we like about magical abilities, but that doesn’t make the stories true.

This is a key difference between the social and physical worlds. People can invent stories and share them far and wide as social reality, but physical reality keeps those stories in check.

Or does it?

Look at what’s happening today with COVID-19. Despite abundant (and tragic) physical evidence, a large group of people nonetheless believes that the deadly virus is not so bad or even a hoax. We have politicians who claim the virus is vanquished when deaths in the country are rising. Beliefs such as these don’t prevent anyone from becoming sick — viruses are physical reality and they don’t care what we think. (All they care about is finding a nice, wet pair of lungs.) But the beliefs persist and spread anyway. People are using social reality to deny physical reality that’s right in front of their faces.

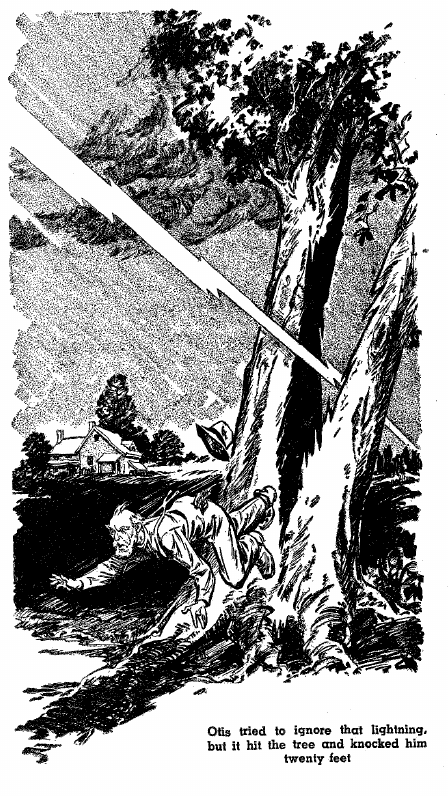

I’m reminded of the 1941 short story “Obstinate Uncle Otis,” by Robert Arthur, about a man who could turn belief into reality just by speaking it aloud. When Uncle Otis denied the existence of an object under his nose, the object would instantly disappear. In real life, physical objects can’t simply vanish from existence; but through social reality, you can make people believe that they’re gone.

Today, social reality has become untethered from physical reality. Partly, that’s because we have so many voices saying contradictory things, amplified by the internet, and listeners might not know whom to believe. When you can’t see the evidence yourself, both information and misinformation can become mere words on a level playing field.

Looking deeper, however, we’re seeing a fundamental erosion in the authority of scientific experts, which itself is social reality. Just as we bestow authority on kings, queens, and presidents by our collective agreement, we do the same for scientists. As a society, we lack agreement today on fundamental issues, in part, because some people have withdrawn their agreement that scientific expertise matters.

This situation is made even more challenging because scientific knowledge is driven by consensus. Very little in science is 100% true or false. Rather, scientists with diverse knowledge and experience look at physical evidence in context and come to agreement on what it’s likely to mean. That agreement is social reality, which means it’s vulnerable to being manipulated or ignored. Moreover, if the public withdraws its consent that scientists are experts in their fields, then we set ourselves adrift in a sea of misinformation without an anchor.

Scientific consensus isn’t always correct; for example, scientists agreed for over 100 years that disease was caused by smelly vapors called miasmas, and they rejected germ theory for decades because they could not sense their own biological residue. Usually, scientific consensus represents years or decades of careful study and vigorous debate. Old, overturned beliefs typically lead to new and better discoveries.

By rights, social reality should be constrained by physical reality. We can all look at a physical body of water and disagree on whether it’s a “pond” or a “lake,” but it’s never a mountain. Nevertheless, someone could upload a viral video that says it’s a mountain, and millions of people can agree that it’s true. And if they try to climb the nonexistent mountain — and drown — then social reality has overruled physical reality to such an extent that people are harmed. On a grand scale, this kind of breakdown might even lead to the collapse of civilizations, a point consistent with Jared Diamond‘s bestselling book, Collapse. When the people who are most responsible for ignoring physical reality are also the most insulated from its effects, disaster may follow.

Social reality is a superpower of human brains acting together. We collectively fight climate change, for example, by inventing “carbon credits” and agreeing they can be bought and sold. But a breakdown of social reality, like calling climate change a hoax, can also bring harm on a worldwide scale. We are all more responsible for reality than we might think. Or want.